Dark Brown

“I have Indian in my family” is something that I’ve heard black people say since I was about 7 years old. I never quite knew what it meant though.

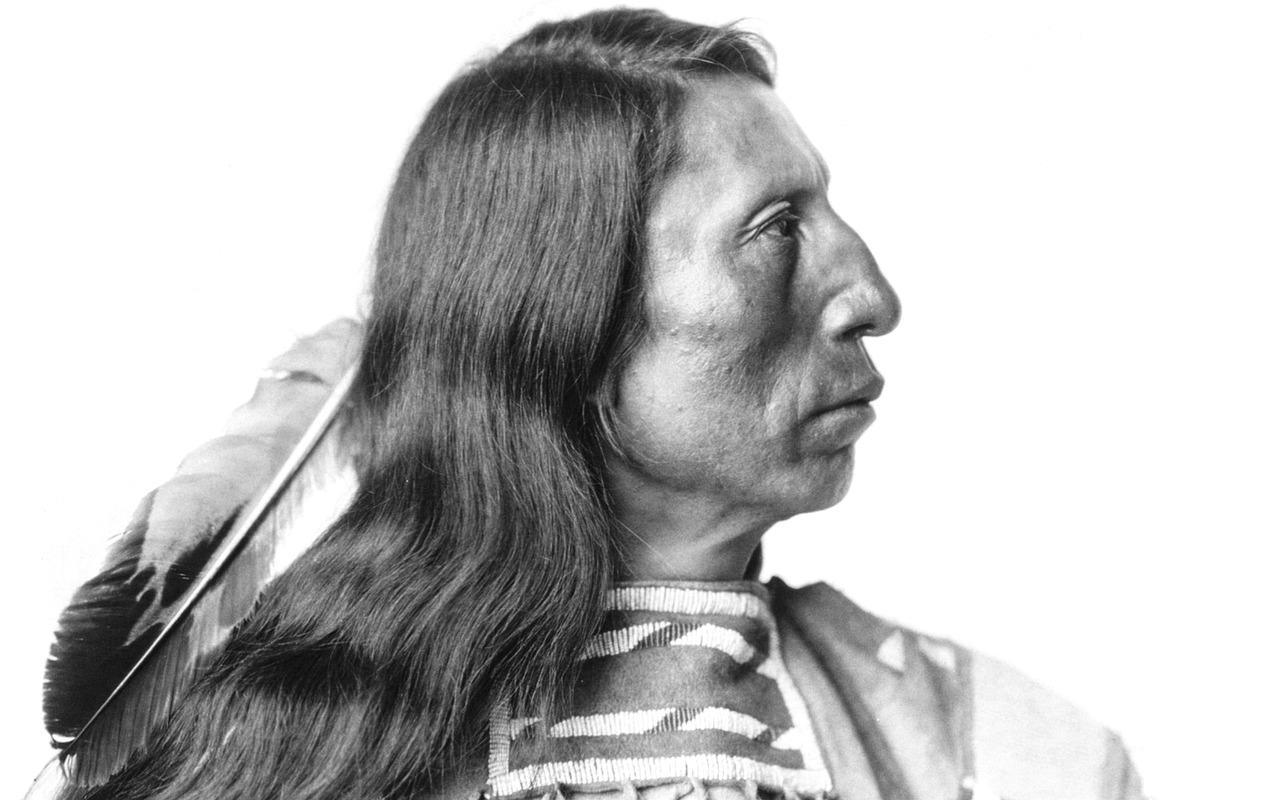

The American media often gives the impression that all Native Americans: 1) were killed off with the settling of America, 2) all live on reservations disconnected from American society, or 3) live off casino money and are unreachable to the majority of tax paying American citizens. It’s almost as if a museum is the only way to see what “real-Iife” Native Americans looked like.

Mainstream media’s representation seems to purposely misrepresent the phenotype of so-called Indians. The American media is largely responsible for Indians being portrayed as caricatures (Redskins logo, Pontiac logo, Cleveland Indians logo) that misleads the public about who these people actually were. To make matters worse, a type of “red-facing” has been done throughout the media, where natives are not even able to represent themselves in places like Hollywood; instead they are represented by europeans who depict their culture and personalities inaccurately. Examples of this are in movies like Last of the Mohicans, the legend of walks far woman, and outrageous fortune.

There seems to be a wide range of visual depictions and descriptions of “Indians” as well. Not different from how Hollywood and the American mainstream media represents Egypt with an inaccurate European twist. This same type of white washing seems to be ever so present with native people from the Americas. So, what do the natives of America look like?

On a quest to find out what indigenous peoples of North America looked like, I took into consideration stories that I have heard, photos I have seen, and accounts people whom are older than myself have told. These findings led me to my grandfather who is in his 80’s, and whose mother was an Indian. What I extracted from him about how Indians and blacks inter-married can be summed up by a few key points:

Indians come in all shapes in sizes, there are Indians that have dark brown skin, or a very earthy red clay complexion, although he did note that the women in our family who were Indian had light brown to high yellow complexions. My grandfather also explained how the inter-mixing of Africans and Native people typically resulted in the loss of culture by the natives because they would take on the dominant American culture. This was especially the case with native women who married African American men.

Believing I had extracted as much useful info from my grandfather as he had available, I searched on and found a book called Portuguese Voyages 1498-1663: Tales from the Great Age of Discovery edited by C.D Ley. In it the Portuguese explorers through letters to the king, describe the native inhabitants of Brazil, India, and Africa using a lot of descriptors. This terminology was applied to indigenous Africans, Indians, and Americans almost inter-changeably. Terms like dark-skinned, Moor, negro, tawny, dark brown, ruddy, and reddish, are used to describe melanated people seemingly indiscriminately of where they were originally from. Distinctions are hard pressed, and the only way it’s known of who they speak, is because the chapters are split by the regions visited.

With everything taken into account it would seem that native peoples from the Americas were more than likely melanated to varying degrees of dark brown like the color of bar-b-que sauce to a golden wheat complexion not unlike the color of a lion. All things considered this would still be dependent on the region and inter-mixing.

Europeans seem to have a fetish for labeling, dividing, and misrepresenting peoples who have different complexions, cultures, and customs other than their own. This type of labeling seems to be something that is done intentionally with the hope to defile the reputation of the groups they are engaged with. It seems very clear that we need to re-evaluate the labels/names given to African and indigenous people by Europeans particularly in regards to racial identity as it coincides with region.

Source

Ley, C. D. (2000). Portuguese Voyages, 1498–1663. Amsterdam University Press.

pages 5,8, 12, 14, 25, 28, 34, 42,43